Dungeon Crawl Stone Soup (DCSS) is the greatest Roguelike of all time.

What is a Roguelike?

Roguelikes are a genre of video games where you play as an adventurer exploring a dungeon. They borrow elements from tabletop role-playing games like Dungeons and Dragons, yet utilize the power of a computer to procedurally generate levels and keep track of the various things a human dungeon master would.

What is so good about Dungeon Crawl Stone Soup?

Games are fun because of the choices we get to make while playing them (if there are no choices, it is a movie and not a video game). We then feel satisfied when the choices we make result in winning the game. This also means that a good game should be difficult- if you win no matter what you do, then your choices are insignificant. This helps explain why people complain when the newer generations of Pokemon games are too easy. On the other hand, some games can be difficult due to unpreventable randomness or a huge time investment in the form of “grinding,” both of which interfere with the creation of interesting and meaningful choices.

Replayability

One of the challenges with game design is making a game that people want to play multiple times (replayability). If the game contains a lot of luck, then people might feel like their choices are not meaningful. If the game does not contain a lot of luck, then there is the risk of a dominant strategy emerging. Once discovered, the game becomes stale since there are no other comparable strategies left- and no choices being made. There are ways around this dilemma. Chess has so many possibilities that most strategies have viable counters (though there is a growing concern that chess could one day be “solved” by computers, like how Checkers has been solved). Many other games have unique starting conditions so that each game is different. Others feature a balance between luck and strategy so that players have to adapt their strategies due to the luck of the draw. And some game designers decided that replayability isn’t so important after all, and created games that are storyline based and only intended to be played once.

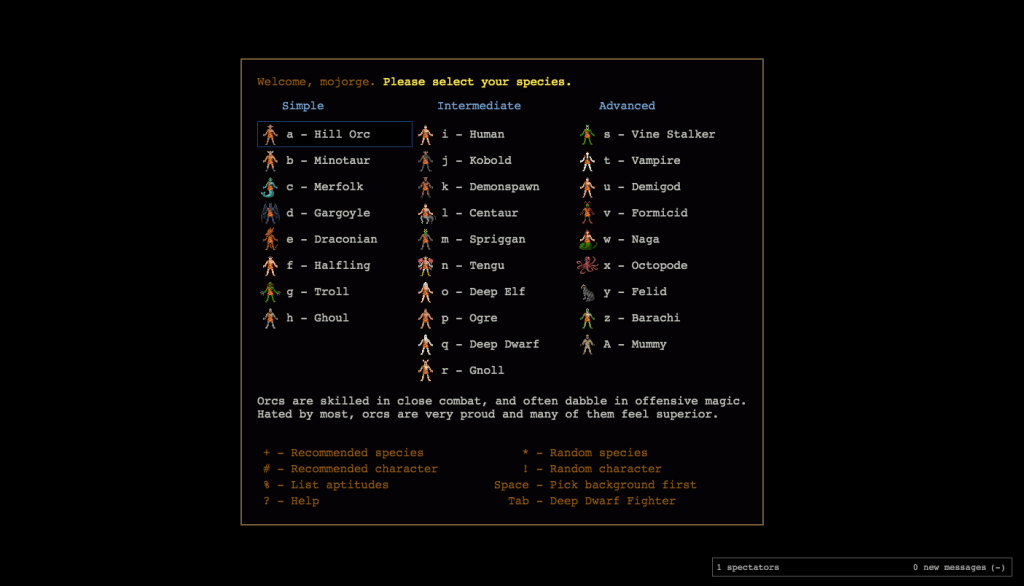

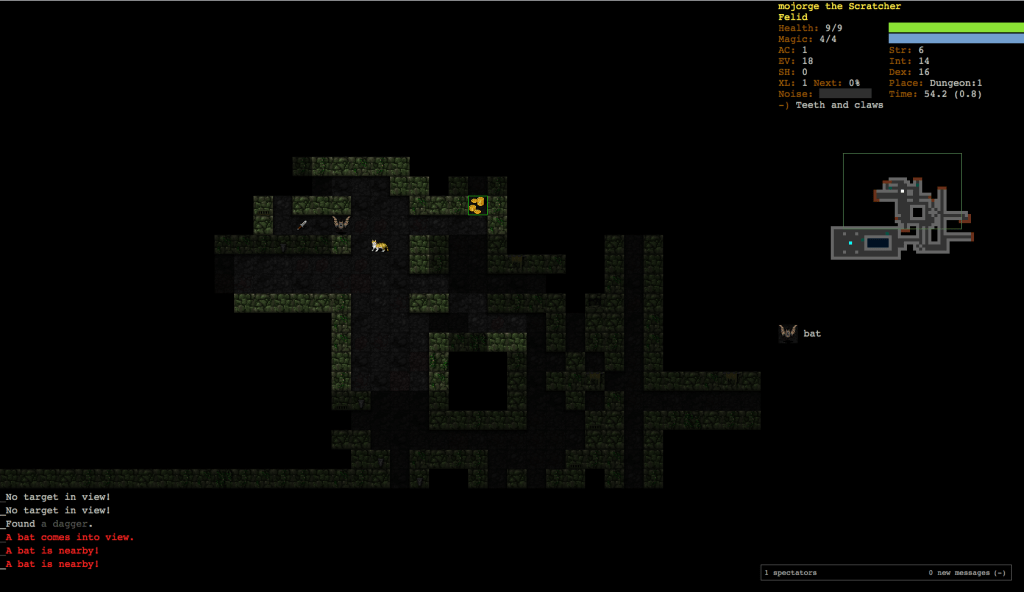

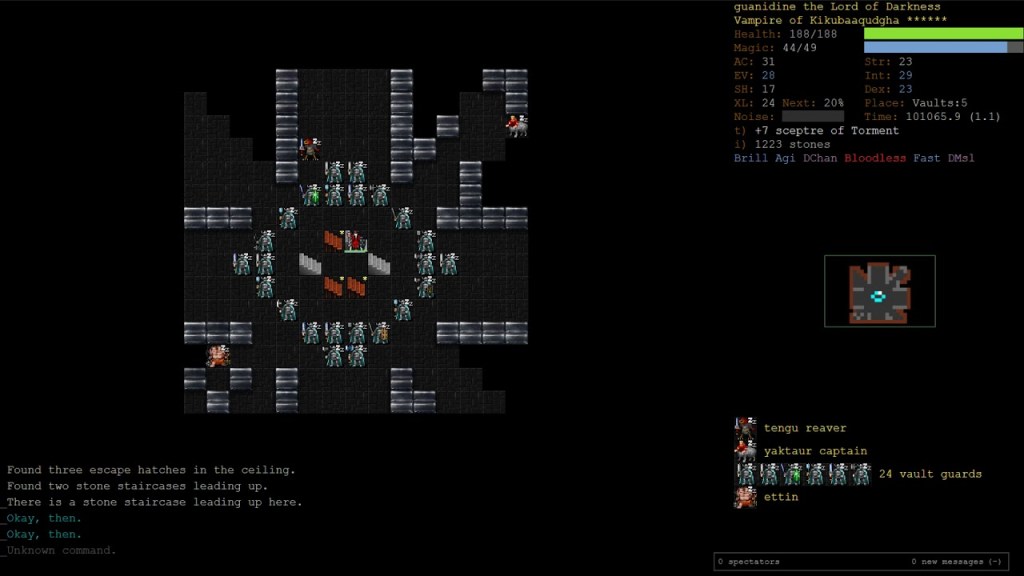

What I admire most about DCSS is the fact that it has almost infinite replayability. The first choice you are tasked with is determining your starting race and class- giving you 648 possibilities within the first few seconds of gameplay. A minute in and you’ll likely have your first dangerous encounter (part of the game design is intentionally putting difficult monsters on each level, often ones that are impossible for low-level characters to defeat), where you’ll have to come up with an escape plan or try to take it on. Luckily, the consumables that you find in the dungeon can be utilized to your advantage. They are significantly weaker than you might find in other dungeon crawlers though, which means that you’ll need to have foresight and use these consumables before you encounter a dangerous situation.

This makes the game brutally difficult, and only about 1% of games played result in victory. Part of the difficulty is the fact that so many of us grew up playing terrible dungeon crawlers. Have you ever played a game where you won and almost never used any of the consumables in your inventory (you never had to: the game was too easy)? Bad habits die hard, and they will get you killed in this game.

DCSS has a lot of luck, but it is the good kind that gives you interesting choices to make, and prevents the game from ever getting stale. Sometimes it is finding a crucial spellbook that causes your pure melee character to consider dabbling in magic. Or maybe you’ll decide that the awesome artifact you just found isn’t worth using after all, because you’ll have to devote too much EXP to mastering it.

Permanent death

DCSS also features permanent death, which means that there are no second chances once your character dies. I normally don’t like this in video games, but it works well in DCSS because of the strategical nature of the game. Only rarely is a death ever not your own fault- and these unpreventable deaths only occur during the first couple floors of the game. Perma-death means that you can’t simply save the game and then act recklessly. While losing is much more frustrating, it means that there are tangible consequences to poor play. It also makes finally winning so much more rewarding.

Tight Gameplay

The gameplay is incredibly tight, and there are rarely moments that are boring for the player. This means that there isn’t any grinding- in fact, grinding often is bad since it means more opportunities to get into a dangerous situation that will use up valuable resources, while granting nearly no EXP. Moreover, the devs eliminated common features in other games that, while thematic, encouraged boring gameplay. A great example is making it so that the player cannot sell useless items to a shop. While it is nice to get a benefit for items that you can’t use, it would encourage collecting useless items just for the sake of a little bit more gold.

Another things DCSS does really well is give the player tools to speed up the gameplay. There is an auto-explore feature that utilizes an AI to let the player travel around an unexplored area. This can be helpful in non-dangerous areas, and it will stop you when you see a monster. There is also a finding feature built into the game that will remember any dungeon features or items that you’ve come across before. You can even easily build your own macros – essentially programming a key to do multiple consecutive actions.

Play DCSS

Interested in playing DCSS? Click the button below to play online for free:

Once you’ve lost a few times, check out Ultravilent4‘s Youtube channel, which is the best way to learn more about playing DCSS well.

Final thoughts

Thanks for reading! What’s your favorite roguelike game? Let me know in the comments.

What do DCSS’s game designers have to say?

Luckily, DCSS developers published their thoughts, which you can find in the how-to manual that you can read in-game. It is hard to find without playing the game though, so I have reproduced it in its entirety here:

“In a nutshell: This game aims to be a tactical fantasy-themed dungeon crawl. We strive for strategy being a concern, too, and for exquisite gameplay and interface. However, don’t expect plots or quests. You may ponder about the wisdom of certain design decisions of Crawl. This section tries to explain some of them. It could also be of interest if you are used to other roguelikes and want a bit of background on the differences. Prime mainstays of Crawl development are the following, most of which are explained in more detail below. Note that many of these date back to Linley’s first versions.

Major design goals:

- Challenging and random gameplay, with skill making a real difference

- Meaningful decisions (no no-brainers)

- Avoidance of grinding (no scumming)

- Gameplay supporting painless interface and newbie support

Minor design goals:

- Clarity (playability without need for spoilers)

- Internal consistency

- Replayability (using branches, species, playing styles and gods)

- Proper use of out of depth monsters

Balance

The notions of balance, or being imbalanced, are extremely vague. Here is our definition: Crawl is designed to be a challenging game, and is also renowned for its randomness. However, this does not mean that wins are an arbitrary matter of luck: the skill of players will have the largest impact. So, yes, there may be situations where you are doomed – no action could have saved your life. But then, from the midgame on, most deaths are not of this type: By this stage, almost all casualties can be traced back to actual mistakes; if not tactical ones, then of a strategical type, like wrong skilling (too broad or too narrow), unwise use of resources (too conservative or too liberal), or wrong decisions about branch/god/gear. The possibility of unavoidable deaths is a larger topic in computer games. Ideally, a game like this would be really challenging and have both random layout and random course of action, yet still be winnable with perfect play. This goal seems out of reach. Thus, computer games can be soft in the sense that optimal play ensures a win. Apart from puzzles, though, this means that the game is solved from the outset; this is where the lack of a human game-master is obvious. Alternatively, they can be hard in the sense that unavoidable deaths can occur. We feel that the latter choice provides much more fun in the long run. Crawl has a huge number of handmade vaults/maps to tweak the randomness. While the placement, and often parts of the contents, of such vaults are random as well, they provide several advantages: vaults offer challenges that are very hard to get via just random monster and layout generation; they may centre on some theme, providing additional immersion; finally, they will often contain some loot, forcing players to decide between safety and greed. (The next topic can also be filed under balance; see Replayability for what balance does not mean to us.)

Crusade against no-brainers

A very important point in Crawl is steering away from no-brainers. Speaking about games in general, wherever there’s a no-brainer, that means the development team put a lot of effort into providing a “choice” that’s really not an interesting choice at all. And that’s a horrible lost opportunity for fun. Examples for this are the resistances: there are very few permanent sources, most involve a choice (like rings or specific armour) or are only semi-permanent (like mutations). Another example is the absence of clear-cut best items, which comes from the fact that most artefacts are randomly generated. Furthermore, even non-random artefacts cannot be wished for, as scrolls of acquirement produce random items in general. Likewise, there are no sure-fire means of life saving (the closest equivalents are controlled blinks, and good religious standings for some deities).

Anti-grinding

Another basic design principle is avoidance of grinding (also known as scumming). These are activities that have low risk, take a lot of time, and bring some reward. This is bad for a game’s design because it encourages players to bore themselves. Even worse, it may be optimal to do so. We try to avoid this! This explains why shops don’t buy: otherwise players would hoover the dungeon for items to sell. Another instance: there’s no infinite commodity available: food, monster and item generation is generally not enough to support infinite play. Not messing with lighting also falls into this category: there might be a benefit to mood when players have to carry candles/torches, but we don’t see any gameplay benefit as yet. The deep tactical gameplay Crawl aims for necessitates permanent dungeon levels. Many a time characters have to choose between descending or battling. While caution is a virtue in Crawl, as it is in many other roguelikes, there are strong forces driving characters deeper.

Interface

The interface is radically designed to make gameplay easy – this sounds trivial, but we mean it. All tedious, but necessary, chores should be automated. Examples are long-distance travel, exploration and taking notes. Also, we try to cater for different preferences: both ASCII and tiles are supported; as are vi-keys and numpad. Documentation is plenty, context-specific and always available in-game. Finally, we ease getting started via tutorials.

Clarity

Things ought to work in an intuitive way. Crawl definitely is winnable without spoiler access. Concerning important but hidden details (i.e. facts subject to spoilers) our policy is this: the joy of discovering something spoily is nice, once. (And disappears before it can start if you feel you need to read spoilers – a legitimate feeling.) The joy of dealing with ever-changing, unexpected and challenging strategic and tactical situations that arise out of transparent rules, on the other hand, is nice again and again. That said, we believe that qualitative feedback is often better than precise numbers. In concrete terms, we either spell out a gameplay mechanic explicitly (either in the manual, or by in-game feedback) or leave it to min-maxers if we feel that the naive approach is good enough.

Consistency

While there is no plot to speak of, the game should still be set in a consistent Crawl universe. For example, names of artefacts should fit the mood, vaults should be sensibly placed and monsters should somehow fit as well. Essentially, this is about player immersion. As such, it’s good to have in mind, but consistency is always secondary to gameplay. A typical example is player vs. monster behaviour: while we try to make these identical (or similar), there are good reasons for keeping them distinct in certain cases.

Replayability

This is actually quite important, but in some sense just a corollary to the major design goals. Besides these, there are several other points helping to make playing Crawl fun over and over again: Diversity whenever there are choices to the player, be that choice of species, god, weapon or spell, the various options should be genuinely different. It is no good to provide dozens of weapons with different names (and perhaps even numbers) if, in the end, they all play the same. Many different species This is partly due to the skills and aptitude system. Similarly important are the built-in starting bonuses/handicaps of species; these often have great impact on play. To us, balance does not mean that all combinations of background and species play equally well! Some are much more challenging than others, and this is fine with us. Each species has at least some backgrounds playing rather well, though. Dungeon layout Even veteran players may find the Tomb or the Hells exciting (which are designed such that life endangering situations can always pop up). These and other branches may or may not fit a given character’s buildup. By the way, we strongly believe that games are pointless if you can reach the invincible state. Religion This addresses new players, as getting to the Temple and choosing a god becomes the first major task of most games. But religion is also a point in favour of replayability for experienced players, since the choice of god can matter as much as species does. Playing styles Related to, but encompassing, species, background, god are fundamentally different playing styles like melee oriented fighter, stabber, etc. Deciding on whether (and when!) to make a transition of style can make or break games.

Out of the depths

From time to time a discussion about Crawl’s unfair OOD (out of depth) monsters turns up, like a dragon on the second dungeon level. These are not bugs! Actually, they are part of the randomness design goal. In this case, they also serve as additional motivation: in many situations, the OOD monster can be survived somehow, and the mental bond with the character will then surely grow. OOD monsters also help to keep players on their toes by making shallow levels still not trivial. In a similar vein, early trips to the Abyss are not deficits: there’s more than one way out, and successfully escaping is exciting for anyone.”